Tags

BCA, Betsy Hodges, Fourth Amendment, Joe O'Brien, Judge Laurie Miller, Justine Damond, Minneapolis, Mohamed Noor, MPD, probable cause, search warrant

In Update 7: The BCA–Gone Fishin’, I wrote of the apparent problems in two search warrants served by the BCA the morning after Justine Damond’s shooting by Minneapolis PD Officer Mohamed Noor, a Somali immigrant much lauded by Minneapolis Mayor Betsy Hodges and the local Democrat political establishment. I was limited in that article by not having access to the actual warrants and related documents, so I relied on various media accounts, including one by Station KSTP which obtained copies of the warrants and asked law professor emeritus Joseph Daly to review them:

I don’t understand why they’re looking for bodily fluids inside her home,’ said Joseph Daly, an emeritus professor at Mitchell Hamline School of Law, referring to one of two recently-released search warrant applications.

‘Whose bodily fluids are they looking for? Is she a suspect? I don’t understand why they’re looking for controlled substances inside her home. I don’t understand why they’re looking for writings inside her home. The warrant does not explain that to me.’

‘When I read that search warrant, I really cannot find probable cause to search her home,’ he continued.

Thanks to a reader who wishes to remain anonymous, I was able to locate the documents on scribd.com. Documents relating to the search of the alley may be found here, and documents relating to the search of the home Justine Damond shared with her fiancé Don Damond are here. I’ll include screenshots of those documents in this article.

Background: There are three documents associated with any search warrant, all filled out by the police:

1) The affidavit, often called the application. In this document the officer lists his experience and assignment, and explains, in detail, the nature of the crime(s), the specific evidence he seeks, where it can be found, and exactly how he came by that information. He must establish probable cause in the affidavit in order to obtain a warrant. He ends by swearing, under oath, everything he says is true.

2) The actual warrant. This is, in part, a copy of the affidavit, but also includes the thing(s) the officers are allowed to search for, where they are allowed to search, any limitations imposed by the judge, and any special permissions granted by the judge. A copy must be presented to the person whose property will be searched.

3) The return. This is the officer’s report back to the judge about what he found, or did not find. All of these documents must be on file with the court. All warrants and paperwork must be done in a short time, usually within a day.

The Search Of The Alley: After Justine Damond died, the BCA was called to investigate and arrived sometime in the early morning hours of 16 July 2017. Shortly after they arrived, they surely knew the basics of what happened, specifically that MPD Officer Mohamed Noor shot and killed Damond shortly before 2400–midnight–on 15 July 2017. Normal procedure for any police shooting requires the officer’s weapon and all ammunition be seized as evidence as soon as possible, and all rounds, fired and unfired, accounted for. This too would have been known to the BCA. Any competent investigator, if not told about all of this, would surely have asked, and would not have been satisfied with “I don’t know.”

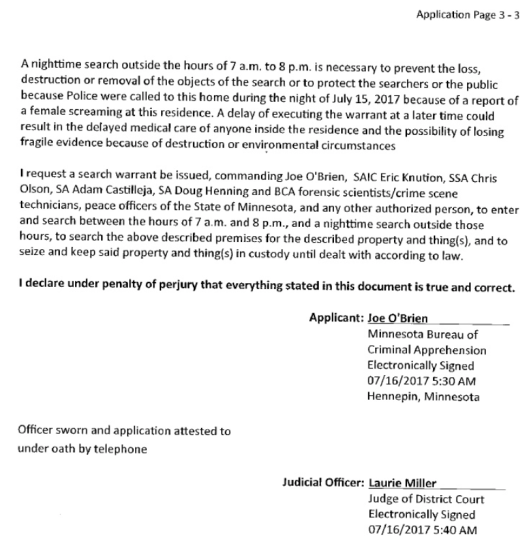

In this case, the BCA, specifically Joe O’Brien, requested and obtained two separate search warrants: one for the alley where Damond was shot and died, and a second warrant for her home at 5024 Washburn Avenue South. These were telephonic warrants. Telephonic warrants are used when there are emergency conditions and it would not be possible to take a written warrant to a judge for him to read and evaluate. The information in the affidavit is read to the judge over the phone, and verbal permission is given. The actual paper copies must be filed with the court later. The paper copies indicate the affidavits were read to District Court Judge Laurie Miller at about 0530 on 16 July. Keep that time in mind, gentle readers.

I’m still not sure why the BCA felt the need to obtain a warrant for the alley–it’s public property–though reader SPD3454 suggests a possibility:

Search warrants on what we think is public property, is common in my jurisdiction. The City maintains the alley and has public right-of-way, but the homeowner technically owns the property to the center point of the alley. This is no different than the sidewalk in front of a home/business. You call it doting the i and crossing T, but I call it covering your ‘rear-end’.

In any case, it may have been nothing more than being certain their search was legally covered, which is never a bad idea in a police involved shooting. Here is the affidavit in three pages:

I am struck by the highly general nature of the property to be searched for and seized. It reads very much like a generic list one might find in a Criminology 101 textbook. Particularly odd is the request to search for “knives and/or sharp instruments,” and writings that might identify a motive or suspect. Damond was the victim. Her motive was to help whoever was screaming somewhere in her neighborhood. O’Brien knew Noor was the suspect. And “saliva swabs?”

The statement of facts is very brief. O’Brien asserts he doesn’t know Damond has a gunshot wound, but also asserts it was an “officer-involved shooting, and would be investigated as such. Why then, does he need to search for “knives and/or sharp instruments”?

Here’s where things become strange. Searches by warrant can normally only be done during daytime hours, but he asks for permission to search at night, claiming the police were called to Damond’s home because a women was screaming there. Not true. Damond reported someone screaming somewhere behind the area of her home. They claim they need to search to prevent “delayed medical care of anyone inside the residence.” It’s 0530. The BCA has been on scene for hours. Are they so incompetent they didn’t sweep the area for potential suspects for their own safety? Did no one think to knock on the door at Damond’s home to see if anyone was there? If they thought someone was injured within and unable to respond, they decided to wait hours for a warrant, and to plead dire urgency only on that warrant? And why would they think anyone was injured at Damond’s home a half block or more away? Didn’t they listen to the 911 recordings during those hours? They could call the dispatch center and have it played over the phone.

Here’s the search warrant for the alley:

Notice that with the exception of formatting differences, it contains essentially the same information as page one of the affidavit.

While the affidavit is non-specific, to say the least, most judges would authorize a search under similar circumstances, and it’s unlikely any judge would exclude any evidence seized under the warrant. Here’s the return:

While the affidavit is non-specific, to say the least, most judges would authorize a search under similar circumstances, and it’s unlikely any judge would exclude any evidence seized under the warrant. Here’s the return:

And here is the “attached,” the evidence seized in the alley. Notice there is little evidence:

Notice “cartridge case(s)” were recovered, but the number was not specified. The police narrative to date is Noor shot Damond once in the abdomen, but this vague entry leaves open the possibility Noor fired multiple shots, hitting Damond only once. The omitted portion of the page is only the signature area. The document does not say when the items were taken into evidence. Presumably the agent’s reports will contain that information, and they have not been released.

The Search Of Damond’s Home: I’ll not post screen shots of this affidavit. Apart from the difference in addresses, it is word for word identical to the affidavit for the alley. Apparently the BCA has a standardized, broadly general, generic form for searches. This does not comport well with the Fourth Amendment:

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects against unreasonable searches and seizures shall not be violated, and no warrants shall issue but upon probable cause [emphasis mine], supported by oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched and the persons or things to be seized.

The affidavit does not “particularly describe…the things to be seized.” It provides, instead, a laundry list of things that might possibly, in some circumstances, be evidence or a crime or fruits of a crime, again, the sort of list one might see in a basic criminology text.

The three pages of the house warrant are, with the exception of the address, identical to the three pages of the alley warrant. This warrant was electronically signed at 0538; the alley warrant at 0540. Here’s the return for the search of Damond’s home:

They found nothing. No blood, hair, fibers, knives, clothing, writings, controlled substances, nothing.

The general nature of the things to be searched for is no coincidence. The police may search anywhere the items they seek might be found. If they’re looking for stolen car tires, they can’t look in jewelry boxes or shoe boxes, but if they’re looking for hairs or fibers or drugs, nothing is denied them.

Analysis: In analyzing such cases, it’s often helpful to look for what should have been done that wasn’t, or for what was done that shouldn’t have been done. Let us assume, for the sake of argument, Agent O’Brien, for whatever reason, made good faith mistakes in his affidavit for this warrant. It was then the job of the Judge–Laurie Miller–to determine whether he had actual probable cause under the Fourth Amendment to search, and if not, to deny the warrant. Here are the questions she should have asked, but apparently did not:

Agent O’Brien, you said Damond was killed in an alley a half block or more away from her home. Why do you think there will be any evidence relating to her death inside her home? Did any of the action in this case take place there?

The answer would be painfully obvious, and for any competent judge, this would be the only question that really need be asked. The affidavit said she was killed in the alley. Her home was separated by time and distance from the place of the shooting in the alley. It had no role in the incident. No role; no probable cause; no search warrant; no additional questions necessary. However, for the sake of illuminating the issues, let’s allow a competent judge to continue:

What crime was committed that has anything to do with that house or vehicles?

Why do you think there would be any trace evidence of any kind in a house a half a block away from the scene of the shooting?

Why would there be any “saliva swabs” there?

Isn’t Damond the victim? If she’s dead, and the victim, why are you looking in her home or vehicles for writings that would identify a suspect and a motive?

What was Damond wearing when shot? Only pajamas? Why do you want to seize all the clothing and footwear you listed on the affidavit? What does it have to do with the case?

Why do you think “papers and documents” in that house would relate to the case?

What do controlled substances have to do with this case?

By the time they asked for the warrant, the autopsy had not been done. They would have had no reason to think Damond was under the influence of drugs or that drugs had anything to do with the case.

Why do you want to search any vehicles on the property? What do they have to do with this shooting?

Don’t you have Damond’s cell phone? Why do you think there are more and why do you think they’re in her home or vehicles?

Why do you think there is “data” relevant to the 911 calls there? What kind of data could that be? Don’t the police have recordings?

If Judge Miller asked these painfully obvious questions, there would have been no warrant, though it would have been perversely amusing to hear O’Brien trying to justify a search. To be fair to the Judge, who I do not know, it is more difficult to deal with the details of a telephonic warrant than a written warrant one can read and reread at leisure. Still…

Obviously, the lists are identical on both affidavits and warrants because they’re generic, not at all specific to the circumstances of the individual crime scenes. In fact, Damond’s home and vehicles were not crime scenes at all, and she was not a suspect.

There was no reason, no lawful, professional reason at all to search Justine’s Damond’s home or vehicles. They had nothing to do with her shooting or death. They were at least a half block away. They were removed from the actual crime scene in time and distance. There was no connection between her home and vehicles and the crime scene. There is no probable cause.

Justine Damond will not be objecting to the search. We don’t know how they searched, whether they tore the home apart, or behaved professionally. Don Damond may have a civil course of action, and this issue will come up in the wrongful death suit he will certainly file.

But the BCA found nothing. Why did they conduct the search? There are two primary possibilities:

Possibility 1: O’Brien and his compatriots are well intentioned but incompetent. They don’t understand the Fourth Amendment and are reduced to using generic, off the shelf forms for search warrants. They didn’t realize they didn’t have probable cause, but wanted to do a good, thorough job and Damond’s home was close by–hey, she made the 911 calls from there, maybe–so why not search it?

Possibility 2: The search was a classic fishing expedition. They knew very well they had no probable cause to search, so they used a generic form to erect a smoke screen, and did an unnecessary telephonic warrant to further obscure the facts. They had no reason not to take the paperwork directly to a judge. They had plenty of time to figure out what happened, and plenty of time to speak with high-ranking MPD and BCA officers. They knew the political climate in Minneapolis, and wanted to be on the right side of that politically correct imperative, so wanted to find anything they could use against Damond to impugn her character or to try to help explain away Noor’s shooting. At the very least, maybe they could give their superiors and high-ranking politicians some wiggle room.

FINAL THOUGHTS:

The BCA arrived at the scene in the early morning of July 16th. This is not a complex case. Even though Noor was not talking–as far as we know–Officer Harrity did cooperate with the BCA, and there is no reason to think that cooperation did not extend to at least a brief version of what happened at the scene. Even if both officers remained mute, it would not take experienced investigators long to figure this one out. They had hours, perhaps as many as four or five. No professional would commit perjury–that’s what lying on an affidavit is–to search a home or vehicle having nothing to do with the case they were investigating.

O’Brien knew it was a shooting case. He knew there was no knife involved. He knew what Damond was wearing. He had her cell phone. He had no reason to think drugs were in any way involved. He knew there were no “writings which may indicate motive and assist in identification of [a] suspect,” because Damond was dead. He knew who she was: the victim, not the suspect. He had no reason to believe virtually any of the things he was asking to search for and seize in Damond’s home would be there. O’Brien knew there was no one “screaming at this residence.” O’Brien knew there was no one in that house in need of medical attention. If he truly believed that, he would have broken in as soon as he came to that belief. To do otherwise would be to knowingly allow someone to die when he could have saved them.

The more conspiracy minded might think the BCA concocted the house warrant on purpose, knowing it was a screw up from start to finish. This would give the local prosecutor, a man with apparently leftist sympathies, an out, a reason to decline prosecution. On one hand, they had no way to know they’d find nothing with which to attack Justine Damond. Surely they believed they’d find something. “Give me the man and I’ll find the crime,” and all that. On the other hand, they found nothing, and the search would have no bearing on the criminal case, so rational people must conclude this possibility is unlikely. Besides, it’s not necessary to ascribe incredible motives when plain old incompetence will do nicely.

This issue is not important because it will be a major legal issue argued in a criminal trial. There is no evidence from the search to suppress. It’s important because the most likely reason for the search is a political fishing expedition. We cannot say this with certainty, but the search raises the question of intent. Is the BCA working to provide a politically palatable out for Mayor Hodges, the City Council, and Mohamed Noor, a black Somali upon who the city has heaped such acclaim? Is it more important to them to protect their political investment in Noor, who represents Minneapolis/Somali relations and Democrat electoral viability, or to uphold the rule of law?

It’s still possible evidence will arise that will make Noor’s shooting of Damond, if not legally excusable, at least understandable. I cannot imagine what such evidence could possibly be. Particularly if Noor is not prosecuted, Agent O’Brien, the BCA, and Judge Miller will have much to explain. They might wish to begin now.

The SMM Damond archive is here.

Mike, is the crime/criminal activity mentioned in the house search affidavit related not to the shooting of Damond, but rather related to the screaming that prompted her calls to 911 in the first place? That is, whether by honest ignorance or intentional misleading, the affidavit asserted that the screaming happened not in the alley, but at the house? And if so, the urgency related to discovering evidence of a potential assualt of an unknown victim?

And, to be valid under 4A, shouldn’t the warrant affidavit have to be clear and specific about such things? I don’t see how the due process and 4A-protected rights of any person would be upheld by this affidavit and warrant. BCA could go on a judge-enabled fishing expedition of pretty much anyone, using this generic affidavit.

I think you’re right about the crime at issue. Reasoning that the screaming was allegedly heard from the house, and since the exact source and location of the the screaming was unknown, they could search the house. It’s a plausible cover for the fishing expedition for something, ANYTHING, that could impugn Damond and exonerate Noor, or find mitigating factors.

Dear Char Char Binks:

That may be their reasoning, except the 911 call could not possibly give a rational person the impression the screaming was coming from Damond’s home. She was quite clear about where it was coming from, and it was not within her home, nor did did she mention her yard. But you’re right; if they do use this to shield Noor, any lie will likely be sufficient to prop up their narrative.

Dear Chip Bennett:

The affidavit for the search of Damond’s home lists the need to find possibly injured victims, and suggests the screams Damond reported came from the house. As I noted, this is false, and there is no excuse for the BCA not knowing it to be false. This is not a complex case with so many facets it’s impossible to quickly grasp them all.

The affidavit should indeed be clear and specific about everything. The Fourth Amendment was written to invalidate all such general warrants, which were in use at the time. With this kind of affidavit, and a lazy/corrupt/incompetent judge, there is no home or other place that cannot be searched without probable cause, and since the generic affidavit requests to search for hairs or fibers, there is literally no place the police cannot search.

Since Damond is dead, and they never interviewed her beyond the 911 call, she couldn’t tell them exactly where the screams came from, so they can plausibly say they were searching for the sexual assault victim, or evidence of same. It’s a reach, but they went for it, and not much can be done about it. Justine Damond can’t even complain, although her fiancé probably will.

It’s called the Bureau of Criminal Apprehension? What might criminal apprehension mean? … My Webster’s says: “2. fear; dread; the thought of future evil, accompanied with uneasiness of mind, apprehensiveness.”

So when one is driving toward the BCA’s headquarters in St. Paul, might a looming dread of its criminality be rather appropriate?

On the other hand, Betsy Hodges and BlackLivesMatter would say our apprehensiveness is what’s criminal.

The aptly-named Bureau is Monty Python material.

—-

Mike — thanks for raising the possibility of incompetence rather than malevolence. The two could be so interwoven here that the mixture itself clouds events.

I ‘d like to add something to Possiblity 2 above. … O’Brien had probably been given a heads-up regarding the impending sh*tstorm even before he arrived at the scene. Upon arriving, if he did NOT subsequently “speak with high-ranking MPD and BCA officers”, then THAT would have terminated his service with the Bureau.

The sun rises in the east. The apple falls downwards. Occam’s Razor says O’Brien communicated, and that he received marching orders. Occam’s Razor says he knew before he set foot in that alley, if he made a misstep, his butt would be grass. And so, O’Brien whored every last shred of his personal honor.

—-

The thought crosses my mind … perhaps the English can be criticized for allowing the art (“art” more than mere skill, a historian once wrote) of drawing and quartering to fade away.

I thought “apprehension” in the name BCA stood for apprehending, that is, CAPTURING and ARRESTING criminals, but I could be wrong.

“Apprehending”, as in capturing, is definition #1 in my Webster’s.

Dear pre-Boomer Marine brat:

Government is the unconstitutional/unlawful things we choose to do together. If O’Brien and his compatriots were acting with the knowledge of his superiors, there is no improper, unlawful, or unconstitutional act they could not do. The fix would be in, and he would suffer not so much as a negative comment on a future evaluation.

True. Instead of strength in numbers, it means invisibility. There will be Tammany involved to bother prosecuting all of them.

Yet again we have someone who doesn’t understand Occam’s Razor. Most folks quote the principle as “the simplest theory is correct,” or something along those lines.

In reality the formation is “among competing hypotheses, the one with the fewest assumptions should be selected.” Your position contains several assumptions, which makes it an undesirable hypothesis.

Even if one does select the hypothesis with the fewest assumptions, there is no guarantee it is correct. The Razor is a guideline, not a natural law.

A proper use of the Razor leads one to the conclusion that our esteemed host has already expressed, that it is too soon to reach any conclusion so far. We just don’t have enough data.

Dear Casey Tompkins:

Quite so, as I’ve repeatedly cautioned. One can forward a preliminary theory of the case with the caveat we don’t have all the facts, but no more.

Have warrants been executed with regard to Mohamed Noor’s residence?

Dear Bill Scott:

Well of course not, you silly person. That would violate the Constitution! Besides, he’s a member of a protected, victim/tribal class.

Hodges: “The strength and beauty of the Somali and East African communities…”

Yes, Betsy. Why don’t you go over there and revel in the beauty at its source? Do you not have the spine?

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-1338479/YouTube-video-Sudan-shows-woman-flogged-laughing-policemen.html

(FYI folks, this particular video is old news, from 2010. The behavior goes back into the mists of time.)

Yes, because Americans would never act that way… {rolls eyes}

If you honestly believe that you are severely unaware of a large part of American history & culture. No, I’m not a snowflake SJW, but I am quite aware of the warts & dirty little secrets of this country. I acknowledge the bad with the good.

I think we all realize we have our own “warts and dirty little secrets.” That’s why many of us would prefer not to be in the Warts and Dirty Little Secrets import business, especially when the PC left insists imported warts are of much higher value than native warts.

Perfection is the enemy of the good. Name a country that ever established, or strove for,or achieved, or conceived of anything greater than USA law, democracy, and human rights.

I’m AMAZED the dirty warrant for Justine’s home didn’t turn up anything. Any little thing at all, a half-empty ibuprofen bottle, could’ve been used to spin a “crazy” or “suicidal” or “drug addled” Justine story to help out the easily startled Officer Noor. I’d like to believe the easily startled authorities in Minneapolis were already running very scared of the local and Aussie backlash, and didn’t DARE cough up something bogus to impugn the character of the murder victim.

I think they were trying to find something to spin her as crazy, but the search of her dwelling came up with nothing.

The whole thing is sad. Justice will not be done until Mohamad is behind bars for a long enough time to gain insight into his malevolence. His life should be taken away from him, not instantly as he did Justine’s, but slowly over the course of a few decades.

He’s innocent until proven guilty.

Justine caused this through her ill-considered naive interaction, beginning with reporting something that she only imagined was happening, and didn’t, then went outside and banged on a police car and approached the window in the dark while they were responding to a “supposed” emergency, that she imagined by overreacting to something on a neighbor’s television or something.

Irrespective of Noor’s possibly being easy to startle, or an affirmative action hire, what Damond did is a dumb thing to do with even the best and most experienced officers, especially in the ambush, and adrenaline-filled environment that exists to today for police.

Sorry, but her own actions put her at great and unnecessary fatal risk, which risk was realized only because she took such risk.

Dear PuttingOnitsShoes:

I’m afraid the known facts do not support your assertions. There is no reason to believe Damond was imagining things. Police officers respond to calls of that type everywhere and every day. You had better hope the legal regime you hope to establish never comes to pass. If it does, the police may indiscriminately murder anyone they claim startled them. All they need do to justify murder is say: “I feared for my life,” or “I feared an ambush.” The actual facts, the absence of actual danger, would matter not at all. On the other hand, it would be very easy to staff police agencies with such people, and they’d work for very little money. Think of the savings for taxpayers.

It appears you want to avoid the obvious truths in this situation, namely, that Justine precipitated out of thin air, a crisis of her own making that resulted in a chaotic and tragic ending for her.

She imagined an “assault” that didn’t exist. There were many houses on the street, and no one else heard anything or called 911.

Subsequently, all evidence indicates that there was no distress or assault that warranted a 911 call to begin with.

She went outside when, by her own statements, a woman was being assaulted. My wife and daughters are trained not to do something so stupid.

She banged on then rushed up on the police with no announcement, while they were responding to an (alleged) dangerous assault, in the dark, with no warning.

The police weren’t “unreasonably” startled, they were just “reasonably” startled because of her really stupid actions.

She was a “faith-healer” which mean she believes in superstitious non-scientific things, and doesn’t fully operate in the “real world.”

She had a complex of seeing herself as a savior, and this caused her to be overzealous in

~first reporting something that didn’t happen (twice),

~second going outside in a dangerous situation,

~third, running down the street after a police car and banging on it,

~fourth running up to the window in the dark with a cellphone in hand.

“If it does, the police may indiscriminately murder anyone they claim startled them.” No it doesn’t, their being under threat needs to have some basis in the circumstances present, and in this case there was a reasonableness to them being more than “startled.”

I can’t expect the police to be able to sort all that out in split second. Civilians need to exercise some common sense around armed emergency responders, who are in the middle of an adrenaline release and believe something dangerous was going on.

I am not worried about a “regime” where such a sequence is problematic. People can’t be dumbshits. I am also not worried, because I would have never done what she did, and neither would my wife or daughters. Don’t you do it, or allow your loved ones to do what Justine did, really I’ll-advised.

You want this to be the police’s fault. It may be that Noor was affirmative action hire (city leaders’ fault then), but he wasn’t out of his mind or grossly unqualified. And this could have happened with someone more experienced.

You are judging the police when you don’t do a job, like they do, where hundreds of on-the-job deaths occur every year.

I am sorry for Justine and her family, but she made an unfortunately set of deadly mistakes. Tragedies are often the culmination of a sequence of independent unlikely events that even more unlikely in their totality. They are rare.

This is tragedy, not malevolence (except for those who use affirmative action to hire mission-critical personnel).

Mrs. Mayor, is that you?

Dear Chip Bennett:

Heh.

I apologize for not reading that you had extensive police experience.

It seems that your belief that the officers didn’t have “good reason” to be startled and in a position too feel danger comes from somewhere.

You seem to have so much training that perhaps your reaction would have allowed Justine to live in these circumstances.

We know that Noor was unholstered prior to her approach, so he was able to shoot quickly. In a holstered situation, this might have been avoided, because identification could have happened in the delay.

Noor was rookie, and maybe the wrong “type” to be police. If that is so, again I blame the PC regime rather than the out-of-control cops regime. Undertrained? probably. Wrong personality type? probably. But they put Noor out there.

I simply don’t believe he shot her for any other reason than he panicked because he thought they were about to be attacked. And she created those unnecessary circumstances.

It will hopefully all come out. I suspect Harrity is surprised and bummed Noor was so quick, but not willing to completely crucify him.

Dear PuttingOnItsShoes:

Thanks. In that situation, were I there, Damond would absolutely have survived. She would have survived had any reasonable, properly trained officer responded. From what we know, Harrity would most likely not have shot her. I’ll address your points in detail this coming week in Update 7.3. Thanks.

You have quite an imagination. I’m not even saying you’re wrong, only that you’re offering reasons without proof, or even evidence. We’ll find out, I hope.

Yes, I have pieced together the available information to come with a likely scenario based on the evidence so far. I dug pretty deep on the available reports, crime scene map, etc.

Yes, I could be wrong, but so far this explanation does two things:

~Best fits the available evidence

~Makes the most “sense” compared to other scenarios being confidently bandied about.

Of course, I absolutely could be wrong, but since we are only in “betting” territory so far, I will “bet” with anyone promoting other scenarios that I am in the right zip code of what happened.

OTOH, Damond was apparently a “spiritual healer”. Although that doesn’t mean she was a lunatic, it certainly doesn’t bar that possibility.

Correct.

Since spirits don’t exist, spiritual healers are hokum. People who have real problems — depression, anxiety, addiction, etc. — should see professionals, not self-proclaimed spiritual healers. Spiritual healers are frauds, whether they themselves know it or not.

So we seem to “know” that she was promoting hokum, either cynically or naively, if reports of her spiritual healer role are correct. I would guess naively, which would explain her naive actions in this case regarding the police.

It seems like a case similar to those folks who think they are “animal whisperers” and get killed by the grizzly or tiger or whatever animal they “believed” they were having a “special” ability to communicate with.

I see very little difference between this case and the cases involving Trayvon

Martin, Michael Brown and the clusterf%&K in Baltimore. Once the political

establishment began to interfere with the investigations indictments, trials

and made it about racial injustice, I predicted the outcomes.

The moment I heard that the great “constitutional law professor” Barrack

Hussein Obiteme prejudged George Zimmerman, I realized that he had

irreparably tainted the jury pool and that the trial would result in an

acquittal. Cory, Mosbey and the idiots who decided to charge officer

Wilson in the Michael Brown case were doomed to lose the moment they

started to shoot their mouths off!

For the record, pResident Mirken Muffly (AKA Barrack Oidiot) was a guest

lecturer in some PC BS subject involving race and gender in the law. In

this case, I am certain that the case has been totally politicized.

I cannot predict the outcome of this particular case, as the racial roles

have been reversed. I am certain of one thing: A black immigrant from

a third world Muslim country is going to have the entire political establishment

circling the wagons to sweep this incident under the rug!

The moment I read that the Minniopolous PD sought warrants to search her

home, I realized that they are reaching for s*&t in an attempt to dig up

dirt in order to protect the man who shot her to death.

There is a reason the term knee-jerk was applied to liberals!

Great article – thank you. What is the rationale for not searching the police officer’s home? The same generic warrant but changed it to the officers address would have been more logical than the victims home. Also, there was nothing listed as being taken from the officer. No gun for rifling testing to match the bullet expended to the bullet removed from the victim. Is there anything in the police investigation policies that require a blood or urine test of the officers involved? Was the police vehicle searched and what was recovered? Assuming the cartridge(s) recovered from the alley were from the involved gun, how did the cartridge(s) exit the vehicle? It makes no sense for the passenger side officer to reach across and discharge his gun across the stomach area of the driver position, have the cartridge eject from the semi-automatic and end up outside the vehicle. Unless it bounced around inside the vehicle, off the windshield, stearing wheel and landed on the driver clothing and fell from him as he exited out to the alley? Assuming one cartridge(s).

Pingback: Why was a Search Warrant issued for Justine Damond's Home the morning after she was shot & killed by Somali cop Mohamed Noor? | Sparta Report

New question – should we assume the state investigation report (BCA or BCI) will not be made public until after the election? Does that bureau report to the governor? If so, who is the Mayor’s political opponent in the Mayor race and could this be used to pound her in the few days leading up to the election? Specifically, if the governor or bureau chief can influence the timing of the report release to draw votes away from the leftist mayor to a more moderate mayoral candidate? it that plausible or am I all wet?

I didn’t slog through your whole post…I only got through your analysis of the affidavit for the residence, so you may have posited this possibility later and I didn’t get to it…if so I apologize…things to see, people to do.

The first thing that strikes me is your presumption that the police should arbitrarily rule out other possibilities simply because of the information they have at this point and assumptions associated with that information:

To wit: The 911 caller reported screaming outside her home, the affidavit stated “at the residence” it didn’t say inside or outside, just “at”. Should the police assume that the information about the screams coming from outside were accurate? Or should they check to see if anything happened inside the home? I’d say it’s perfectly legitimate for them to check to see if anything went on in there.

You seem to think that because they acknowledge an “officer involved shooting” they should have just assumed that the victim was shot by the cop and not injured in some other way. Yes, they knew that the officer had fired his gun, but should they just automatically assume that his aim was true and that he actually hit the victim, or would it be legitimate for them to with-hold judgement on that point and investigate all possibilities…i.e. that the victim had been injured before approaching the car and the shot(s) missed? I’d say that scenario is very unlikely…but impossible? No. Worth checking out? Yes.

If they don’t make any assumptions about whether the victim was injured by gunshot and entertain the possibility, however unlikely, that the victim was injured elsewhere and/or by other means and just died at the scene (provided that the officer’s shots missed), wouldn’t it be a legitimate line of inquiry to check the house to see if there’s any evidence there that the victim was injured inside the house before coming out?

The only thing I find problematic in this whole thing is approving a search for drugs. As far as anything I’ve seen, there was no probable cause to believe that drugs were involved so that should not have been included in the search warrant…however I think it’s likely that you’re right in that this department just has a general search warrant form they use in some (or all) situations that just provides a laundry list of the things they generally search a crime scene for. I’d contend that this is a bad policy but it wouldn’t surprise me if it’s something that happens in a lot of jurisdictions.

Be that as it may, I think your insistence that the investigators should not pursue certain lines of inquiry in a case like this because they should make certain assumptions based on the information they have at this point is fatally flawed. In this case, the probable cause to believe a crime had been committed was laying on the ground in the alley. It was pretty clear-cut. At that point, the investigator’s job is to look into all possibilities to determine what actually happened and rule out any other possibilities, however unlikely.

Let’s say they never searched the house and never made any determination that there was no evidence of foul play there…let’s further say that forensics was unable to definitively match the bullet in the victim to the cop’s gun (very likely considering he was likely using hollow points which deform or break apart on impact). During a trial, what competent defense attorney wouldn’t raise the possibility that the victim had been shot before ever approaching the Police vehicle? How could the investigators deny this possibility if they never investigated it?

I’d say searching the house was just covering their bases and being thorough. I see nothing nefarious in this.

I know you were a cop and your perspective from that standpoint is highly appreciated in these types of stories, but were you ever an investigator or detective? The thought processes of an investigator are quite different when trying to not only gather evidence of the crime, but to also “think outside the box” and eliminate all possible lines of “reasonable doubt” into what actually happened.

Just to be clear, I’ve never been an actual cop, but I was in Naval Security during one tour in the Navy. During that time, I served as a patrolman, as the Patrol Supervisor and as an investigator. Granted, the level of criminality on naval installations and surrounding areas aren’t exactly comparable to what civilian police deal with (we dealt with a lot of petty thefts and assaults…homicides, not so much), but the techniques and principles involved are very much the same…in fact we often trained with the local police departments to better hone both our skills and theirs, so I do have a passing familiarity with the principles involved.

Most of the time your commentary is spot-on with my limited experience in the field, but in this particular case, I think you’re reading way too much into it.

Time will tell.

Your analysis and questions require the police’s ignorance of several points of fact that were, in fact, available to them, some five hours after the shooting, when the affidavit was written and the warrant request made.

Dear Sailorcurt:

I’ll address your concerns in detail this coming week in Update 7.3.

Let us not exclude the most likely culprit, Police Paranoia. Thanks to President Clinton and the gun control lobby, many police suffer from a Freudian Phobia of being outgunned by the criminals. President Obama’s incitement resulted in multiple mass shootings of police officers in 2016 that has forced many honest and courageous to fear that they are being targeted.. It is well understood that unreasonable fear can provoke an overreaction.

Yes, this had a role, and the word paranoia is not quite right, since there are actually people how to get them.

African-American males rather than blonde, white women.

Come on, you know it was dark and she rushed up on them. Their lights were out. I don’t know how dark, but probably shot at a person in the dark rather than a “blond” woman.

A bleached woman — how about that?

Also, your comment starts a discussion on the psychological fitness of any given police officer for the position, in this case of course Noor’s. I acknowledge, Noor may have been psychologically or temperamentally unfit for the position, his cultural background perhaps a factor in his psychological/temperamental development.

Also, I am sure there are many officers (most?) who wouldn’t have shot Justine in this situation. But damn, was it dumb for her to do what she did.

Last thing I will say before your next update is the following:

I am thinking of this from the perspective of keeping oneself safe in imperfect and hectic situations. Living in a semi secluded area with lots of wildlife, and some armed home invasions in recent months, we have had extensive family discussions about behavior in certain scenarios.

In addition, we had a middle of night alarm trigger with Sheriff response. One of the things we talk about is to make sure we don’t do something that confuses responding officers to think we might be “bad guys”.

When I am on the road, the girls know under no circumstance to go outside if there is some sense of danger, or if police are in the middle of a response.

We also have fire arms as last resort, so the awareness to make sure one never presents as a “threat” to responding LE is high in our household. Wife and I both tactically trained for weapons we have.

Been pulled over at night for speeding, and am so super careful to keep hands visible and move correctly and only at right times, etc.

So my perspective is that the world is imperfect, and some cops should be better than they are. But since they aren’t all, we try to proceed in light of that imperfection to keep ourselves safe.

If my wife or teenage daughter had done what Damond did (and lived), I would be super upset with them for taking the risk.

Also, really wonder what you think about Noor being unholstered while in car, not sure how that fits in with proper procedure. That accelerated the pace, and perhaps that was a protocol breach that will make him more culpable.

Also, my understanding is the bike passed on the passenger side of the car (from back of car to front) nearly simultaneously with the “slap” by Damond on driver side, possibly adding to Noor’s confusion.

You make some good points. I’m still on the fence on this Noor/Diamond matter.

Damond, of course.

Yep, despite all I have proffered as possible scenarios, I don’t have all the facts and am happy to have a complete picture if we ever get one. So I would say I am on fence too, even if I may have seemed strident.

Mike seems to be saying that the public is also “imperfect” and police need to be able to deal with that, and not let that be an excuse when stuff goes really bad. That seems to be on target.

If he is right, it is a matter of how imperfect Damond’s behavior may have been. Perhaps, despite all the “goofy” stuff (in my view) that she did, it shouldn’t have threatened (or taken) her life.

I am also super-intrigued, because I think the public deserves a clear explanation of what happened and why.

With typical narratives inverted on this one, makes it extra-important for us to get clarity.

Dear PuttingOnItsShoes:

I haven’t seen anything about a bike rider being near the police vehicle. Do you have a source?

Yes, I had a source when I plowed through several documents last week that were linked through local Minnesota reporting. I will go back and see if I can dig up a link and, if so, repost here with the link. I am in CA and likely can’t find until after work today PDT.

http://kstp.com/news/officers-though-ambushed-in-alley-south-minneapolis-shooting-justine-damond/4546095/?cat=1

It is hard to exactly piece together from the sources, but it appears that it passed in front of the vehicle, as they approached 51st and they were watching it go by right as the pounding happened, so not as close to the vehicle as I had pictured when I first read through this stuff.

Quoted from article:

“The officers had responded to a report of a possible assault. After not noticing any activity, they were dispatched to another call when a young man rode past on a bicyle along 51st Street. “As the officers watched the bicyclist cross the passenger side of the vehicle, they heard the pounding noise on the driver’s side, the source said.”

Harrity, who was driving, told BCA investigators that “Officer Noor discharged his weapon” from the passenger side of the vehicle.

Noor had his gun in his lap at the time, according to the source.

The source said the bicyclist stopped at the scene after the shooting and videotaped the aftermath.”

Looks like it is unclear what it means “cross the passenger side of the vehicle” but it clearly states the bicycle was on 51st, and the vehicle was still in the alley, so not as close as I described above and not “from back of car to front” as I had pictured when I first read “cross the passenger side of the vehicle.”

I have also read the vehicle was 10-20 feet from 51st at the time of the shooting.

Dear PuttingOnItsShoes:

Yeah, saw that article and similar articles. Obviously, the bike rider was on a crossing street, not the alley, and apparently had no effect on the officer’s perceptions or actions. I suspect “cross the passenger side of the vehicle” means traveling, as in crossing a “T” from the driver’s side to the passenger’s side. Thanks for checking into that.

Last thing. I can’t find the dang map I saw last week that showed the relative location of everything, but it was clear the location of the vehicle was not directly behind Justine’s house, but had proceeded well up the alley toward 51st at the time of the slap.

That is why I picture Justine waiting behind her house and then running up to the cop car from behind, from her house’s alley location to the vehicle location.

Do you have the map that showed all that?

I also wonder why they would have given the “all clear” signal without going to the Justine’s house and interviewing her, before leaving the scene with an “all clear”.

Also, it says they had received a new call and were “leaving” to respond to a different call.

Pingback: PowerLine -> Is the Times a law unto itself? And, The Week in Pictures: White House Daze Edition – Hoax And Change

Mike, this article has a video of the alley about halfway down the story.

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-4737564/Justine-Damond-U-S-Mohamed-Noor-never-face-charges.html

Dear Sue:

Thanks!

Pingback: Justine Damond: Rights And Responsibilities - Watcher of Weasels

Pingback: The Justine Damond Case, Update 7.3: Rights and Responsibilities | Stately McDaniel Manor

Pingback: The Justine Damond Case, Update 7.4: Police Searching Police | Stately McDaniel Manor

Pingback: Damond: Police Searching Police - Watcher of Weasels

Pingback: The Justine Damond Case, Update #9: Transparency And Accountability | Stately McDaniel Manor

Pingback: The Justine Damond Case, #13: Cops Interviewing Cops? | Stately McDaniel Manor

Pingback: The Justine Damond Case, Update 13.3: What Happened? | Stately McDaniel Manor

Pingback: The Justine Damond Case, Update #16: A Reasonable Police Officer | Stately McDaniel Manor

Pingback: The SMM Top 15 Of 2017 | Stately McDaniel Manor

Pingback: The Justine Damond Case, Update 33: Police Glory | Stately McDaniel Manor

Pingback: The Justine Damond Case, Update 34: Duty and Courage | Stately McDaniel Manor