The first three updates in this series—Update 20, Update 20.2 and Update 20.3—have exposed the manipulative, underhanded, unethical and incompetent interviewing techniques Metro used to establish and maintain its narrative blaming Erik Scott for his killing at the hands of three, panicky, uncontrolled Metro officers at the Summerlin Costco in Las Vegas on July 10, 2010.

All of the statements of Metro’s chosen witnesses are remarkable in one way or another. Particularly striking is the persistent lack of curiosity–on the part of the detectives conducting the interview—of anything having to do with Scott’s handgun. The moment a witness mentioned anything to do with it, or even appeared to be about to mention it, the detectives changed the subject. Also striking is their inability to ask even the most obvious questions, or to ask ridiculously apparent follow up questions, all of which made the statements incompetently brief and incomplete.

Most disgusting is the fact that Metro played an unethical trick, potentially on everyone with whom they conducted a taped interview. After conducting an interview, they pretended their tape recorder malfunctioned thus forcing a second interview. This is the refuge of scoundrels, for it allows them to manipulate and change the interview and to deal with anything they don’t want to record off the record. Most people won’t know what has happened and will not realize they were manipulated. Even so, as in the case of John Cooper outlined in Update 20.3, some few citizens strained to include the truth, obviously causing the detectives great discomfort.

In considering these statements, it should also be remembered that Metro officers, rather than taking pains to ensure each and every potential witness was identified and interviewed, actually chased many of them away. The sheer number of witnesses discouraged from speaking will never be known, but the initial lawsuit filed by the Scott family did have the effect of encouraging some of them to come forward. Such was the case of Eileen and William Nelson.

“Get In Your Car And Go Home!”

Eileen Nelson did not complete a written statement, but she did write a letter to Metro, a letter dated July 12, 2010. I’m pasting in a copy of that letter, which by all means, I recommend you read in its entirety.

This section is particularly important:

Officers #2 and #3 began shooting as Mr. Scott was falling and after he had landed on the pavement. The officers fired at Mr. Scott multiple times. Mr. Scott landed on his right side looking in my direction. I saw him take a last gasp and not move anymore. His left eye was open and glassy. It appeared to this writer he was dead.

An officer then handcuffed Mr. Scotts hands behind his back. At no time were vitals taken.

Then officers began telling people to move back behind the police cars.

I stood up from where I was sitting in shock and said ‘I saw it ALL, what should I do?’ to which officer #4, whom the dark haired woman [Samantha Sterner] was trying to get to stop the shooting, looked at me and said ‘get in your car and go home!’

I did not observe Mr. Scott fire a shot nor did I observe a weapon in his hand, I only saw the holster. The holster was on the pavement before the many shots were fired by officer #2 and #3. This writer truly believes Mr. Scott was shot to death unnecessarily.

Due to what the officer told me I have hesitated to come forward with a statement.

I have always respected the police and the work they do, BUT I am 72 years old, I have never seen an execution style killing of a person like this in my life! He did NOT have to die, because he made the mistake by not complying with metro’s demand, BUT metro made a bigger mistake by forcing the issue amonst [sic] so many people in a confined area.

On 07-27-10, Detectives Calos and Jensen conducted a taped interview of Elieen Nelson and her husband, William. As I noted in Update 20.3, professionals never conduct interviews of two people. This exchange is particularly interesting:

Q: Okay. Did you see anything in Erik Scott’s hand?

A: I did, sir.

Q: What was that?

A: A brown object. I cannot identify it because I was looking at it this way, I saw the back of his hand. He had something in it, but I—at that time I could not tell you what it was.

Q: Okay.

A: As he began stumbling back [after being shot] he dropped that object to the ground, it was a brown holster, near a telephone, cell phone.

Q: Okay. Was there anything in the holster that you saw?

A: I could not tell, sir.

As is usual for the detectives investigating the Scott case, when any mention of a weapon is brought up, or when the narrative is in danger, they immediately change the subject, interrupt the witness, try to put words in the witnesses’ mouth, or otherwise obstruct. Immediately after Eileen’s answer, they changed the subject, but tried to return to it later:

A: But not until…okay, the first officer shot, Erik was stumbling back, lifted his arm, and then dropped whatever it was he had in his hand. And it was the brown holster.

Q: Okay.

A: Just to my left was another officer, and a dark haired woman came around and was pulling at him to stop, try and stop what was going on, and she kept yelling, ‘He’s got a permit. He’s got a permit to carry.” Just then, as Scott was still stumbling, and as he fell to the ground, then the other officers started shooting, one right after another, multiple times.

At this point, the detectives were obviously very anxious to change the topic:

Q: Okay. Now…

A: But Erik’s hands were empty. He had dropped what he’d already had in his hand. They were empty and up in the air when he was stumbling and falling backwards.

Again, the detectives changed the topic, but toward the end of the interview, Eileen—and William–managed to get in the opinions she expressed in her letter: Scott was unnecessarily shot and the officers were foolish to shoot him in the middle of a crowd they created through their poor tactics. In fact, Calos abruptly shut off the interview when William Nelson was in the middle of making a statement. No doubt by then Calos was desperate to end it as the Metro narrative was in tatters. The end of the interview reveals their desperation:

WN: [William Nelson] ______(both talking) [William and at least one detective], if you’re gonna, ah, confront somebody with a bunch of people, I mean a taser would have been much, ah, more within the line of public safety, that would be a 9 millimeter, or whatever he’s using. Okay? Uh anyway, uh, to me, if he’d a just, a couple officer just followed him on out. He was walking out casually, you know, and got him out here, away from the people, then confronted him. To me that would have been a better scenario.

Q: Okay.

WN: I’m…

PC: [Det. Pete Calos] I have no more. Thank you.

Q: [Det. Jensen] All right. Secretary, this will be the end of the statement. Date and time of statement is 07-27-2012 at approximately 1440 hours.

WN: you’re six minutes ahead of me.

Despite the detectives, William Nelson got in the last word, which suggests he believed the detectives were not accurately keeping track of the time of the interview, which in turn suggests Nelson was keeping track of it himself, obviously not trusting the detectives.

Eileen Nelson was one of the many citizens who saw what happened to Scott who were unceremoniously ordered to leave without identifying themselves or giving their statements. As I’ve previously written, any competent police supervisor learning of one of his officers doing that would be, in short order, removing large chunks from their posterior. Particularly since three officers shot a citizen, failing to identify and interview every witness no matter how little they knew, the behavior of the officers is shocking and inexplicable. Unless, that is, this is how Metro routinely handles officer shootings: not to gather all possible evidence to come to an accurate and just conclusion, but to construct a narrative that will always exonerate Metro, which has been the case for decades.

What did Eileen Nelson see? Scott’s holster was very plainly black—not brown—and if the Metro narrative was right, his handgun must have been in it, and clearly visible from virtually any angle. What is known without any doubt is that Erik Scott had his Blackberry in his right hand, which is where he always carried it. We also know, without any doubt, that Scott dropped it when he was shot, and Nelson saw it on the ground near his body. She also believed she saw the “holster,” but given the time frame, and the fact that we know Scott’s Kimber and holster were discovered on his body in the ambulance, the only thing that could have dropped from Scott’s hand to the ground was his Blackberry, which was also black in color.

[Scott] Was Empty Handed:

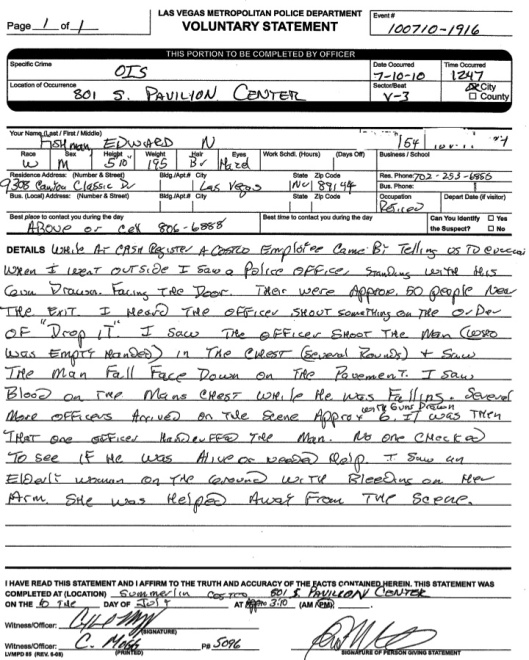

By chance, a physician, Dr. Edward Fishman, was present at the Costco that day. Here is his written statement:

Notice the bottom section of the statement form. Unlike many of the written witness statements, this particular document is properly filled out and witnessed by the officer administering the statement, in this case, a Detective Mogg.

The written statement is concise—as one might expect of a physician—and unusually detailed. Fishman not only saw Mosher challenge Scott, but saw him shoot him, correctly noted Mosher fired “several” shots, saw blood on Scott’s chest as he was falling (Mosher’s first round struck Scott in the heart), and noted that even as Mosher said “drop it,” Scott was empty-handed. As a physician, his concerns were also for Scott, and he noted that after Mosher handcuffed Scott, he was rendered no medical assistance. No one so much as checked his pulse.

Detective Mogg conducted a taped interview of Fishman at the Costco on 07-10-10 at 1640. Unlike many of the Costco patrons, Fishman was not told the evacuation was due to a man with a gun, and so his observations were not shaded by the expectation that Erik Scott must have been armed. Like most of those giving a statement, he saw an officer waiting at the door with his handgun already drawn and seeing that, decided his original impression of a bomb threat was likely mistaken.

Fishman repeated his observation of hearing Mosher order Scott to “drop” something. This exchange is illustrative:

A: He was a white male and I think his hair was blonde. That’s not what stuck out in my mind. I heard, ah, um, one gunshot, then I heard I think it was two more, and I saw this guy [Scott] fall to his knees, and I saw blood on his chest, and he fell down, face down.

Q: Okay. You said you saw him reaching to his side.

Mogg is putting words into Fishman’s mouth. Fishman did not say he saw Scott reaching to his side in either his written or taped statements. As is common in such matters, Fishman misses this in the flow of the conversation and continued:

A: Yeah, and I remember seeing his shirt up, I saw skin in that area.

Q: Which side?

A: It would have been his right side.

Q: Okay. Did you ever see anything in his hand?

A: No.

Q: Did you see him raise his hand toward the officer?

A: No.

Q: Did you maintain constant visual contact with him from the time you heard the officer saying drop it, or something to that effect?

A: I was looking in that direction. You know just so much was going on at that time. You know it’s not really what you would expect. A few were screaming. Um, I, I heard people, you know, saying run, you know just in the crowd.

Q: Okay. Were people still exiting the store as this was going on?

A: There were people all coming, there were people all over the place.

Not getting the proper responses to support the narrative, Mogg tries again:

Q: Okay, so how long do you think it was between the time the officer said drop it, and you saw the suspect reaching for his right side?

A: It was all in the same time frame. I couldn’t time it. It might be seconds.

Q: Okay.

A: You know, it was real fast.

Q: And what about between the time you saw him reaching for his side and the shot was fired?

A: That was, it was all in the same, it was seconds. It just happened so fast.

Notice that Mogg has now manipulated Fishman into agreeing that Scott somehow was “reaching for his side.” Fishman has not caught the manipulation, and as people commonly do, is merely helping to keep the conversation going while still trying to clarify his points.

Fishman doesn’t recall other officers shooting Scott, but does recall additional shots, though he is not sure how many. Interestingly, this means his focus was on Mosher and his shooting of Scott, the most crucial events in the incident. Mogg tries a third time to fulfill the essential elements of the Metro narrative:

Q: Okay. And could you tell whether or not the suspect was complying with what the officer told him?

A: It just happened so fast. See I don’t know what drop meant, if he had something in your hand to drop it. Maybe the guy was going here to, to pick it out, then drop it. Maybe the guy was going to pick it to, to shoot at the officer.

Q: Okay.

Notice that Fishman’s statement here is unclear at best, yet Mogg doesn’t ask clarifying questions. He’s content to get anything on the record that might help Mosher and Metro. However, Fishman isn’t being completely cooperative:

A: I don’t know. Uh, what was scary to me when all this was going on, there were just so many people there. I mean such close proximity. That’s the thing that bothers me the most about it all, ‘cause it could of been tragic, you know, not only for the suspect, which is was, but you know for anybody else. There was women, kids, you know, everybody there.

Q: Okay. Um, so you don’t know what the suspect had in his hand, if anything?

A: No, I don’t. Once again, I just saw a shirt being raised. I don’t know if he actually had his hand, you know, on the gun. ‘Cause I didn’t see a gun.

Q: Okay.

A: But…

Mogg is obviously not happy with the direction Fishman is heading and interrupts him in the hope of salvaging something:

Q: After the suspect was down on the ground, did you see anything lying around the suspect?

A: No.

Q: Okay. Did you stick around in that area, or was everybody cleared out?

A: I stuck around in that area…

Dr. Fishman also testified at the Inquest, and his testimony must have given the prosecutor fits. During his inquest testimony, Fishman said:

It [Mosher’s yelling at Scott] was all very confusing. I was hearing commands, “Drop it, drop it’ is what I thought I heard. And there was nothing in Mr. Scott’s hand to be dropped.

Fishman also testified that after Mosher handcuffed Scott and abandoned him, Fishman stood watching, upset that no one was trying to take his pulse or render any kind of aid. He also testified that despite remaining there and looking carefully, he saw no handgun—nothing—on the ground near Scott. Fishman also testified that Scott never acted in a threatening manner toward the officers, but Fishman was so intimidated by their behavior he did not try to approach them or offer his medical services.

Unlike another witness, the prosecutor at the inquest did not savage Dr. Fishman who was obviously a sympathetic and believable witness. The witness the prosecutor did savage was local public defender Howard Brooks.

The Man Who Knew Too Much:

Howard Brooks completed a detailed written statement at the Costco. Unlike many of the other statements, this one was properly executed by a Metro officer:

Notice that Brooks was told there was a man with a gun, but this knowledge only prompted him to observe more closely to determine the truth or falsity of that claim. In fact, Brooks dropped off his purchases in his car and seeing many officers and a police helicopter, returned to see what was happening. Standing 15-20 feet from Mosher, he saw Mosher yell “drop it’ and immediately start shooting.” He writes:

The interval between the warning and the shots was less than a second. It seemed immediate to me.

Most telling is this passage:

(10) The man who fell to the ground [Erik Scott] –I never saw him hold a gun. I never saw him do anything.

(11) When the first officer shot 3 times another officer fired at least one shot at him. The man fell to the ground. One shot was fired at him when he was on the ground. I think but am not sure that a fifth shot was fired.

(12) It is a miracle that no one else was shot. The crowd around the victim was that big.

A taped interview of Brooks was conducted by Det. Bunn at the Costco on 07-10-10 at 1545. His taped statement is very much the same as his written statement, but adds detail, such as this passage:

Um, I then [after Scott has been shot and is face down on the ground] circle around to the right hand side of this stuff to watch what’s going on. The man is lying, what I perceived to be face down on the ground, and I do not see anywhere around him a gun. Now please understand I did not, I don’t have any idea what happened inside Costco. I don’t know what the police officer saw, but I cou—I never saw this man with a gun. I never saw him move in, in any way. It was my perception that he was coming towards me when the police officer shot him from behind with the first three shots. Ah, it was very scary.

Brooks said Scott was only three or four feet from Mosher when Mosher shot him. Det. Bunn asked:

Q: Okay. Did you ever here [sic] the man make any response, or was it only the officer that ever said anything_____ (both talking).

A: I, I did not hear any response. I only heard the, ‘Drop it.’ And I might add, the shooting started immediately, so it was just, he didn’t have time to respond if in fact he made a response. I don’t know if he made a response.

At the Inquest, it was almost immediately apparent that the prosecutor, a Mr. Owens, would treat Brooks as a hostile witness. Considering Brooks was one of Metro’s handpicked witnesses in a hearing with no opponent and a pre-determined outcome, this was an extraordinary and bizarre turn of events.

The direct examination turned into a cross examination when Owens tried to get Brooks to testify to a snippet of the 911 tape he happened to hear on the television sometime before the hearing. Owen was trying to get Brooks to say, after he heard Moser say “drop it,” Mosher also said “get on the ground, get on the ground.” When Brooks refused to cooperate, saying he would testify only to what he heard, Owens testified for him, and the judge allowed it. The point was Owens was trying to counteract Brook’s testimony that Mosher fired immediately after saying “drop it,” hoping to suggest that more time elapsed, which would tend to make it possible for Scott to have drawn and pointed his Kimber at Mosher before Mosher fired.

Owens then tried to impeach Brooks by suggesting he was somehow not adhering to his taped statement in saying he was watching Scott and Mosher. Brooks was able to explain how Det. Bunn played the “my tape recorder wasn’t working” trick and his second statement was less detailed than his first the detective pretended wasn’t taped. Brooks was able to explain that his first statement was more detailed. Owens immediately accused Brooks of being biased against the police, an incredible way to treat one’s own witness.

Shortly thereafter, Owens tried to shut off Brook’s testimony, but by appealing to the judge that he knew a great deal more, Owens was forced to ask Brooks to continue. This was his testimony:

Okay. Once the first shots occur, that’s when there is complete pandemonium. People running, screaming, everything. At that point, the crowd completely disappears in front of me. And officer two and three [Stark and Mendiola] come up.

They proceed—at this point, Erik Scott is falling to the ground on his face. He is either on the ground, or he was falling to the ground, and officers two and three commence shooting him as he’s falling on the ground on his face.

I saw both two and three with their guns in a downward position. I couldn’t see any reason in the world why these shots were being fired. Officer two shot at least once, maybe twice. I don’t know. Officer three shot at least once and maybe twice. But in my opinion, the shootings by officers two and three were completely gratuitous.

If the officer one [Mosher] had not killed him, it seemed to me clearly that officers two and three were making certain he would not be alive. He falls to the ground. I then circle around beside the first officer, trying to look at the body.

And I see Scott lying on the ground. He is not moving at all. He’s facedown with his face to the left. He left arm is flat where I can see it. His right arm is under his body. I don’t see a gun anywhere around him. That’s what I was looking for. But I could see the bullet holes in the back.

At that point now, other officers are running in saying, ‘get back,’ and I proceed to leave.

Owens did, through his hostile questioning and his changing the topic, manage to keep Brooks from directly saying that he never saw Scott touch, draw or point a gun at Mosher. Unfortunately for Owens, an interested party later asked if he ever saw a gun in Scott’s hand or on the ground, and Brooks said he did not. A juror asked:

A JUROR: Okay. Did you find any of the actions of Mr. Scott unusual in respect to the demands that the police were giving him?

THE WITNESS: I never—I never heard any demands place on him, except to drop it. So I don’t feel qualified to say. I mean I feel certain this man—it looked to me before the shooting starts, he’s just walking out of Costco, not doing anything. I think if the officers had followed him to his car and had a conversation with him, none of this would have happened.

After Brooks was finished with his testimony, Owens once again did his best to point out every minor discrepancy in his statement, something that was not done with the other witnesses who all supported the Metro narrative.

FINAL THOUGHTS:

How do we—how do the police—determine who to believe? As I’ve demonstrated in the four articles of this series, even Metro’s handpicked witnesses do not agree with each other—or with the facts—in most cases. In matters great and small, those seeing the same event came away with very different stories.

For competent police officers and agencies, the gold standard is evidence. To what degree do witness statements comport with the evidence, with indisputable facts? Competent officers know witnesses are often wrong, sometimes ridiculously wrong, but they must also trust their instincts won through years of experience, instincts that may help them decide who is more credible. Ultimately, however, the facts must prevail, for if they don’t, if mere belief or perception carries the day, we are not a nation of laws and of proof beyond a reasonable doubt, but of proof by weight of numbers and law altered to fit circumstances.

As I previously noted, I don’t have any evidence to believe any of these witnesses were maliciously lying. However, it is clear that a number were predisposed to believe the police and to see them as knights in shining armor. It is equally clear that Metro’s tactics were successful in manipulating and altering the perceptions of other witnesses, and because of the “aw, that darned tape recorder didn’t work again” deception, we’ll never know precisely how many statements were contaminated or to what degree they were changed, though I suspect that virtually every one was, to at least some degree. Notice how even Dr. Fishman was tricked into seeming to agree that he saw Scott raise his shirt even though he never actually said or even implied that.

In the Erik Scott case, clearly we cannot believe the Metro narrative, a narrative that relies on incompetent police tactics, disappearing evidence, illegal searches and seizures, a rigged Inquest and police internal review system, the manipulation of witnesses, threats and harassment and implausible and impossible actions. Las Vegas is hopelessly corrupt and has been for decades. Therefore, any witness statement that supports that narrative must be discarded as mistaken or even deceptive. To understand that witnesses could be completely wrong is not a matter of taking sides, but of recognizing and accepting reality.

Consider then the Nelsons who did not see a gun in Erik Scott’s hand and consider the detective’s treatment of them, their desperation to end the interview before they did too much damage to the narrative. The detective’s actions alone suggest strongly the Nelson’s accounts were all too accurate, and all too destructive to the narrative.

Consider Dr. Fishman, a physician whose attention was focused precisely where it would provide the greatest chance of accurate perception. As a physician, Dr. Fishman is a trained and experienced observer of human beings, and unlike many of the other witnesses, he was not predisposed to see a gun in Scott’s hand. He looked closely, before and after the shooting and not only did not see a gun in Scott’s hand, he did not see one on the ground after he was shot, and he is not at all vague or unsure about his observations, nor does he overcompensate to try to hide or justify indecision.

Fishman was particularly struck by Mosher’s “drop it” command because he could plainly see Scott had nothing in his hand to drop (Scott may have already dropped his Blackberry when he was initially confronted by Mosher), and he was thinking just that at the time. He also noted that Scott was making no hostile or threatening motions when he was shot. Fishman, of all of the witnesses, was by far one of the most accurate in recounting the time frame from Mosher’s first command to the first shot.

Consider attorney Brooks, who made it a point to return to the front door of the Costco to observe what happened there. His account of the shooting closely mirrors Fishman’s, and like Fishman, his accounting of the time frame is accurate. Most significantly, he realized that Scott would have had no time to respond to Mosher’s conflicting commands or to draw a gun. Like Fishman, he did not see Scott make any threatening motions, and was certain Scott never had a gun in his hand.

Many other witnesses failed to see a gun on the ground near Scott’s body, but no other witness did what Brooks did: he maneuvered around Scott’s body, specifically looking for a gun. Brooks made a determined effort to find a gun on the ground, but found none. As my theory of the case—and Metro’s own evidence—proves, Brooks was right. As Brooks was looking for a gun, Scott’s handgun was still in its holster, in his waistband, under his shirt.

To experienced, professional police officers, the Scott case remains a “how not to” textbook with the most outrageous, graphic examples and illustrations imaginable. I hope these articles have contributed to the layman’s understanding of what the police can be as well as what they must never be.

As much as I enjoy reading these, can you trim them down. I don’t have time to read 20 pages each post. i.e. I appreciate you re-stating stuff, but just have 1 line with a bunch of links and get to the new meat please (i.e. tap recording tactics paragraph).

I do appreciate you making us aware of this case. Knowing what happened to a West Point grad makes me incredibly thankful for our local police and aware of what I might run into.

Overall I think the content is good, I just need it more focused as times since I already spend enough time reading blogs :-)

Dear Robert Zaleski:

I very much appreciate your comments. In cases like the Scott Case, the Trayvon Martin Case and the Jose Guerena Case, I find myself in a bit of a situation. They absolutely require in-depth coverage, which is one of the strengths of blogs as opposed to the Lamestream Media, but as you note, sometimes length can become a bit of a problem. The choice I sometimes end up facing is to post an article longer than I would prefer, or cut it into two shorter articles. We both know the advantages of shorter articles, but when you’re trying to keep alive a train of thought or reasoning in a complex case, cutting it in half is often counter-productive, almost requiring readers to revisit the older article to refresh their memory to fully understand the sequel.

I guess the best I can do in this kind of situation is to make a choice and hope it works for most readers. Might I suggest reading half–or so–of such posts and returning to the next half when you have the time? I usually leave longer posts up for a week.

Thanks again, and I’ll keep your concerns in mind!

Mike, This is not a reply to the above, but more a direct question to you.

If I made a discovery (in the National Archives), and it could rid us of our original Republican sin (Watergate), would you be interested?

I believe the Liberal media could be pushed off its moral high ground if my novel “Watergate Fiction” had us all revisit “the Lessons of Watergate”

Would you be interested in me sending you a copy … to start this quest?

Doug Reed

Dear Doug:

That’s fine, but I can’t promise when I’ll be able to get to it, and I make no promises about what I’ll be able to do, but I’ll take a look.

Reblogged this on clarkcountycriminalcops.

It has been great following the Scott and Zimmerman cases on your site. Any consideration doing something on the Downs Syndrome case in Frederick Md where they handcuff Ethan Saylor over a $12 movie ticket and he died in their custody?

http://articles.washingtonpost.com/2013-02-19/local/37180924_1_deputies-law-enforcement-theater-employee